50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Lambert Beauduin and the Liturgical Movement (11)

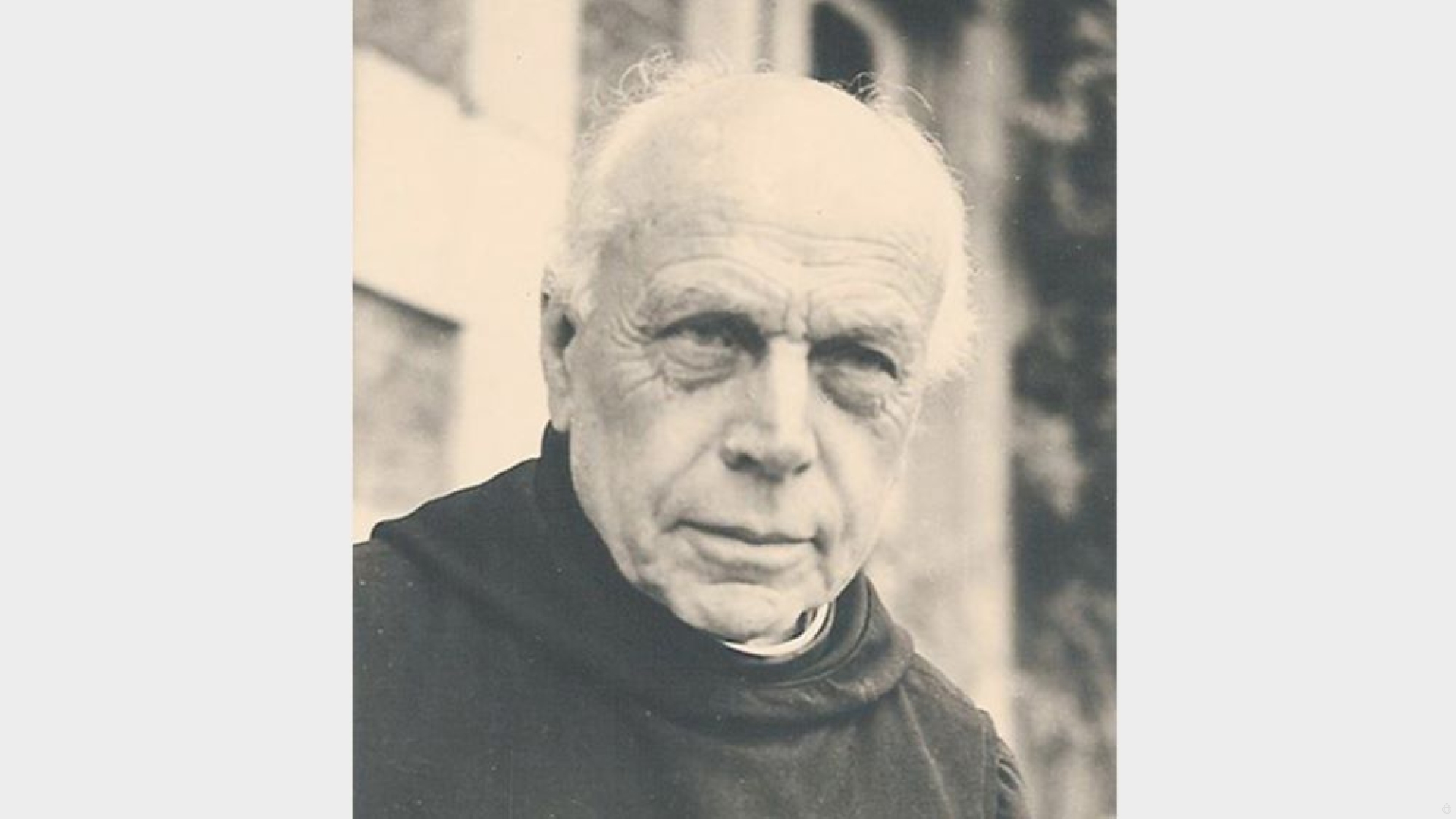

Dom Lambert Beauduin

Octave Beauduin was born in Rosoux, Belgium, on August 4, 1873. At the great Liège seminary, he was strongly influenced by Fr. Antoine Pottier, who was very attached to the workers’ apostolate and the encyclical Rerum Novarum. He was ordained a priest in 1897 and appointed supervisor and teacher at Saint-Trond. Starting in 1899, however, he joined the diocesan congregation of the Society of Labor Chaplains, founded five years earlier. He carried out various responsibilities in this young and modest congregation, principally that of running a house in Seraing where, with other priests, he undertook an apostolate with the laborers.

By nature, Fr. Beauduin was an active and enterprising man: according to the testimony of Canon Gaspard Simons in 1947, on the occasion of Dom Beauduin’s priestly jubilee, “his personality and temperament showed a rare need to be everywhere, to work hard, to act.” However, Fr. Beauduin was also attracted to a life of prayer and contemplation. Partly uncomfortable with the evolution of the Society of Labor Chaplains, and at the same time eager to find a way to quench this thirst for the interior life, in 1906 he entered the Benedictine monastery of Mont-Caesar, which had become an abbey in 1899, near the University of Leuven. At the monastery, he was given the name Lambert, under which he would henceforth be known.

Benedictine Monk at Mount Caesar

In the monastery, especially through the splendor of the ceremonies, Dom Lambert Beauduin discovered the spiritual richness of the liturgy, which until then had not constituted the center of his piety. Reading The Liturgical Year by Dom Guéranger along with the oral teachings of Dom Columba Marmion, the monastery’s prior, particularly made a mark on him.

A series of unforeseen circumstances led him toward the study of the liturgy, notably a meeting with the faithful on February 2, 1909, where participants assisted at a solemn liturgy using a booklet prepared by Dom Beauduin in which all texts had been translated into French. In his short speech of thanks, the lay leader on this day cited a sentence, from Pius X’s Motu Proprio of November 22, 1903, on active participation in the liturgy as the first and indispensable source of the true Christian spirit. This excerpt from a text of the Holy Pope would become the standard of Dom Beauduin in his liturgical crusade. He would go on to make, as his official biographers write, “a true machine of war to propel the liturgical movement” (R. Loonbeek and J Mortiau, A Pioneer, Dom Lambert Beauduin, Editions de Chevetogne, 2001, I, p. 68).

By his temperament, by his previous commitment to the Society of Labor Chaplains, Dom Beauduin was essentially a man of action, as already stated; and he saw things from the action point of view. Observing (what was an already widely accepted truth) that the faithful, and even the priests, did not dwell long enough on the great texts and great actions of the liturgy, he wanted to work open up the texts and actions to these people. There, too, he joined many other predecessors and contemporaries. But his first pragmatic orientation, which his few months of Benedictine life could not correct, led him to a deviation that would vitiate his entire liturgical activity.

Mount Caesar was a monastery under the obedience of Solesmes. For Dom Guéranger, the liturgy was first and foremost a worship of God, to whom is due “all honor and glory throughout all time.” If he wanted the faithful to rediscover the riches of the liturgy, it is so that they could be more authentically, “worshipers in spirit and truth demanded by the Father.” Of course, Dom Guéranger was aware that educated frequenting of the liturgy would form more convinced, more spiritual Christians, and he was delighted about it. But this is only a secondary consequence. Because, for him, a Christian, by his baptism, is essentially consecrated to the ‘praise of the glory’ of the Holy Trinity, which makes his sanctity and, through that, will make him happy in Heaven. This is the reason for the striking introductory phrase of his Liturgical Year: “Prayer is for man the first good.”

Primacy of Action and Pastoral Care

Dom Beauduin, of course, does not question the theocentric orientation of the liturgy. However, according to his pragmatic temperament, he approached the liturgy primarily as a means of making Christians more Christian. It is in this sense that the Liturgical Movement which he would powerfully help to launch (even if he was far from being the only promoter) in its spirit is a “Pastoral Liturgical Movement.” The Center opened in France in 1943 in line with his ideas would not be called the “Liturgical Center,” but truly characteristically, the “Center for Pastoral Liturgy.” Of Dom Marmion, whom he yet highly esteemed, his official biographers tell us, Dom Beauduin also wrote with a certain disdain that he was not a “pastoral apostle of the liturgy,” and that there were “holes in his liturgical life”(I, pp. 49-50).

If the first purpose of the liturgy is to form and inform Christians, it would be advisable for these latter to be able to follow it more easily. The obvious first step would be the translation of the texts along with explanatory notes: Dom Gaspar Lefebvre’s St. Andrew Missal perfectly represents this step, but it is only a prerequisite for Dom Beauduin’s great design.

Then, logically, it would be even better if the liturgy were put directly into the vernacular, so it could be understood immediately. Also, contemporary people no longer have time to assist at long ceremonies, therefore, it would be useful to simplify and shorten the liturgy. Finally, a certain number of the rites coming from the Middle Ages seem difficult for modern minds to understand, so, it would be suitable to reconstruct the liturgy, at least in part, to make it more “transparent,” easier to understand.

A Revolutionary Program

Translation, simplification, reconstruction of the liturgy: these are the three main axes of Dom Beauduin’s approach, to which he referred under the name of “pastoral liturgy.” This is the program that would be implemented in the Second Vatican Council’s Sacrosanctum Concilium, the constitution on the liturgy (December 4, 1963) and by the post-conciliar liturgical reform led by Archbishop Bugnini under the close control of Pope Paul VI.

Evidently, it was impossible to propose such a revolutionary program out of the blue—the mentality of the time certainly would not have accepted it. It was necessary to delay, to present things in a scattered way, work behind the scenes, use all the right opportunities. But it is just that orientation which will be the guiding principal of Dom Beauduin’s activity as it was that of his disciples and imitators.

Dom Beauduin laid the cornerstone of his project in 1909 in a speech he gave at the National Congress of Catholic Action in Mechelen, Belgium, which he called, “The True Prayer of the Church.” His official biographers summarize this intervention as follows: “The starting point of the argument is the familiar thesis drawn from the first pontifical act of Pius X: ‘The first and essential source of the true Christian spirit is found in the active participation by the faithful in the liturgy of the Church.’...The liturgical renovation is essential, because the Christian people cannot draw the expression of their prayer or the nourishment of their spiritual life from the liturgy. The renovation work will be slow and arduous… The liturgical texts, with a literal translation, must become popular among all the faithful… His argument very logically leads to the feeling that action needs to be taken” (I, pp. 80-81).

From that moment Dom Beauduin devoted all his strength to implementing this program of transforming the liturgy. But then came the First World War, which slowed down the work. Then, as early as 1921, Dom Beauduin’s main interest turned to ecumenism, to work on a “Union Monastery” (today in Chevetogne, Belgium) [a Christian unity project]. Even if he remained the figurehead of the liturgical (pastoral) Movement, he no longer participated much: his disciples and admirers had taken over. Dom Lambert Beauduin died in Chevetogne on January 11, 1960.

Related links

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Gaspar Lefebvre and His Missal (10)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: St. Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (9)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Making of the Roman Missal (1)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Saint Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (7)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: St. Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (8)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Fr. Emmanuel, Parish Priest of Mesnil-Saint-Loup (6)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Guéranger and the Liturgical Movement (4)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Guéranger and the Liturgical Movement (5)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Tridentine Missal Put to the Test by Gallicanism …

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Development of the Roman Missal (2)

(Source : FSSPX - FSSPX.Actualités - 08/02/2020)