50 Years of the New Mass: Maria Laach Abbey (13)

L’abbaye de Maria Laach

Maria Laach Abbey is a German Benedictine monastery located in Glees, in the Rhineland-Palatinate. Founded in the 11th century, the abbey has remained active, except for a time during the 19th century when it became a Jesuit scholasticate. Returning to its Benedictine vocation in 1892, it is now part of the Beuron congregation of the Order of Saint Benedict. It brings together most of the male and female Benedictine houses in the German language.

The abbey was the center of the Liturgical Movement in Germany. It organized “practical” liturgical weeks and conferences, along with publishing books. It was from within its walls that Dom Schott’s Missal, the German equivalent of Dom Lefebvre’s, came out in 1921.

Dom Ildefons Herwegen (1874-1946)

Dom Herwegen entered Maria Laach Abbey in 1894. He was elected abbot in 1913 and remained so until his death in 1946. In 1918, he launched the Ecclesia orans collection (The Church in prayer) which would appear until 1939. The aim of this review was very commendable: to bring German Catholics, broken by war, back to liturgical piety. The initiator also spoke of a “liturgical effort.” It was not aimed at the masses, but rather sought to form an elite.

Unfortunately, the ideas he sought to promote in this liturgical “effort” are most disastrous. Dom Herwegen believed that the liturgy should be freed from the elements added in the Middle Ages which cluttered it with fanciful interpretations or developments foreign to its profound nature, e.g., the insistence on the real presence of the Holy Eucharist was more or less responsible for Protestantism’s abandonment of the liturgy. He also disliked a certain liturgical negligence of the liturgy in a large part of Catholics as a whole since the Council of Trent.

Dom Herwegen also thinks that the Middle Ages turned away from an objective mode of piety, which represents the piety of the Church, in favor of a subjective and personal mode, which represents the piety of the individual soul.

These two ideas came form the basis of two serious errors which are diffused throughout the German liturgical effort: archaeologism which results in contempt, not only for the Tridentine liturgy, but also for the medieval liturgy; and a tendency to form a collective piety, think collectivist. These two errors will be found later.

Dom Odo Casel (1886-1848)

This other Maria Laach monk is much better known than the previous one because of his theory concerning the mystery of Christian worship. He had a very important influence on the constitution on liturgical theology which was to triumph at Vatican II and come out in the New Mass.

According to traditional theology, the Mass is first and foremost an act. Tradition unanimously recalls the nature of this liturgical act: it is a sacrifice. This sacrifice is distinguished from that of the Cross, because it is accomplished in a different, unbloody manner, but it is none other than that of the Cross, because it essentially refers to it: “it is one and the same Victim; the same one now offering by the ministry of the priests, as He who then offered Himself on the Cross” (Council of Trent, Session XXII, September 17, 1562, DzH 940); and the Council of Trent immediately adds: “the manner of offering alone being different” (ibid.).

Mass is therefore a present action referring to a past action that it symbolizes. A sensible sign effectively spreading grace, the Eucharist will therefore be called sacrament.

For his part, Dom Casel considers the effectiveness of the sacrament differently. For him, it consists rather in the fact that by symbolically “representing” the mystery of Christ the Redeemer, the sacrament “re-presents” Christ, makes Him present again, and this in varying degrees.

According to this conception, the reading of the Holy Scriptures will be considered as a sacrament. Its effectiveness no longer consists in bringing to our knowledge the supernatural truths so that they become objects of knowledge and love, but in the fact that its “being read in Church” makes Christ present.

It is in the same manner that the Eucharistic liturgy is sacrament: because, under the veil of symbols, it makes Christ present in His redemptive acts. This new interpretation of the word sacrament by Dom Casel is considered by Cardinal Ratzinger as “the most fruitful theological idea of the 20th century.” Such an interpretation cannot be made without undermining the very nature of the Mass: the action of Christ Sovereign Priest immolating Himself on the altar has disappeared in favor of a static presence. Such, according to Odo Casel, is the heart of the liturgy: “The celebration of mysteries presents itself thus as a religious office ordered with art which leads to the ecstatic contemplation of the divinity.”

Therefore it is no longer an effective presence, the saving grace of which is being “applied to the remission of those sins which we daily commit” (Council of Trent, DzH 938), but a presence inviting us to contemplation. The price of such a utopia is immense: we have sacrificed to it the immolated presence of Christ acting for us in the omnipotence of His redeeming love!

According to the traditional conception, Christ is the only high priest: it is He Himself who performs the unbloody act of immolation which defines the Mass. The priest is the same at the Cross and at the altar, the only difference being that at the altar, Christ offers Himself “by the ministry of the priests” (DzH 940). The priest is therefore also the cause of the act of oblation of Christ at the altar: an instrumental but real cause. He holds this power by his priestly character, without sharing it with any other (Summa, suppl. Q.40, A.5).

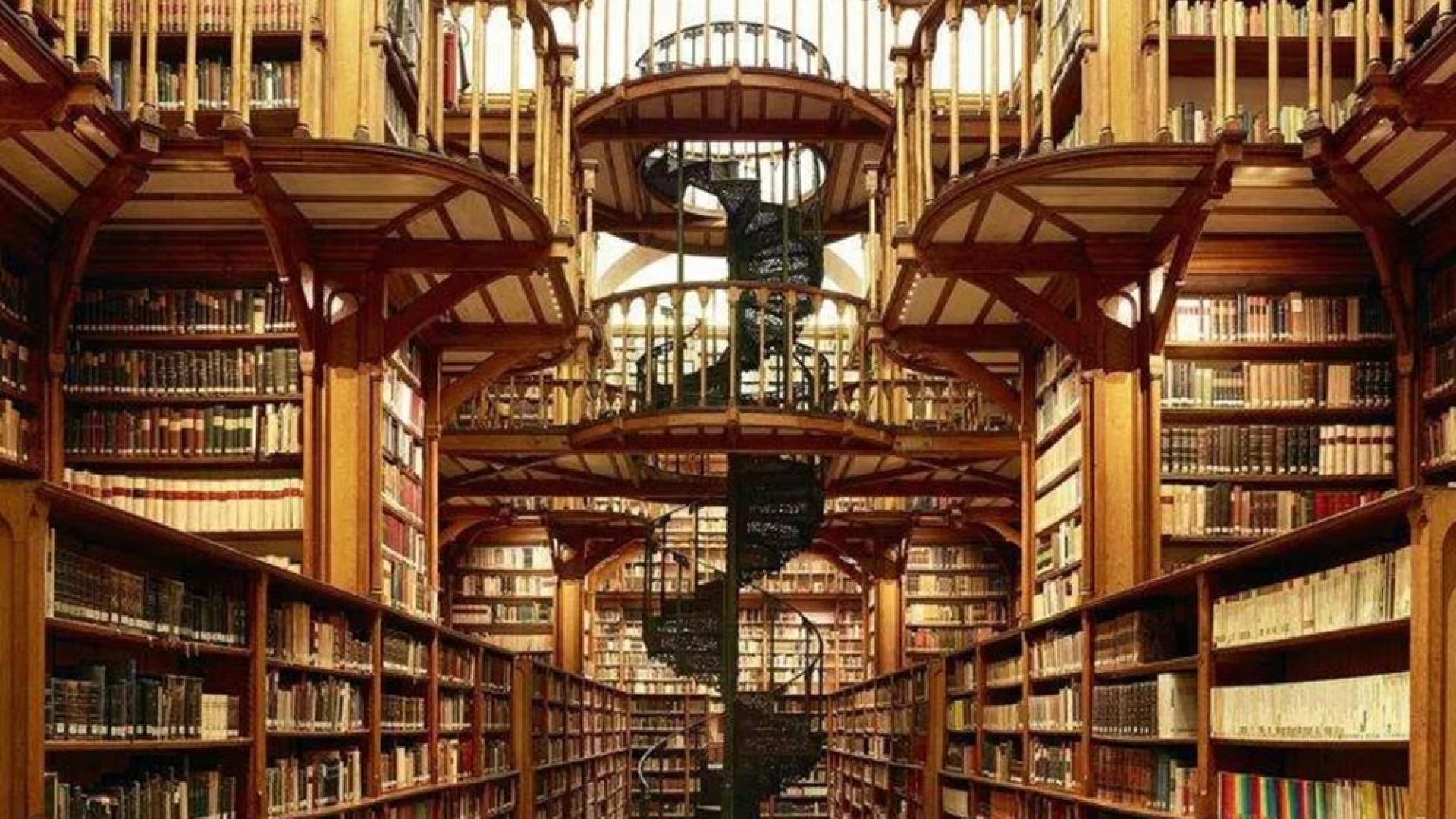

Abbaye de Maria Laach, la bibliothèque

And not only does the priest act in persona Christi at the altar, but he also carries within himself, at this same moment, the entire Church: “inasmuch as he who offers it acts in the name of Christ and of the faithful, whose Head is the divine Redeemer” (Pius XII, Mediator Dei, no. 96, November 20, 1947), that is, in persona Christi but also in persona Ecclesiæ. Pius XII tells us that the minister at the altar represents not only Christ who offers Himself as a pleasing victim to the Father, but also “in offering a sacrifice in the name of all His members, represents Christ, the Head of the Mystical Body. Hence the whole Church can rightly be said to offer up the victim through Christ” (Mediator Dei, no. 93).

Theology adds another mode of participation in the sacrificial offering of Christ, which Pius XII calls “limited.” Thus, those who assist at the liturgical sacrifice—the priest celebrant or the laity—give themselves interiorly in union with the divine victim. This action falls under the baptismal character. It is then that the Church speaks of the “priesthood of the faithful,” which is not exercised exteriorly and in a liturgical manner, but interiorly and in a spiritual manner; its proper object is no longer directly the Eucharistic sacrifice, but only the sacrifice of oneself.

In the new theology, but this is not specifically Dom Casel’s theory, this second mode has in fact supplanted the first. Henceforth, it is the priestly assembly—all the faithful having the common priesthood—who perform the Eucharistic rite.

It is therefore first and foremost the assembly which is called “celebrant.” According to the new theology, it is no longer the priest who, as minister of the Church, acts in its name. From now on, the Church makes herself present and acts through the assembled People. Here we find an additional application of the new sacramental theology, which is supposed to “make present” the reality signified. The People, in coming together, become the symbol making present the universal Church, its sacrament.

It is therefore through the People, as assembled, that the action of the Church is exercised. It is to this that the neo-theologians appeal when they speak of a common priesthood in the Church.

A New Theology of the Mass

What then is the action accomplished by this new priesthood? Let us listen again to Odo Casel: “The whole liturgy is nothing other than a remembrance of the acts of the Lord in its objective sense. (…) If this keystone were removed from the liturgical edifice, the whole construction would fall apart and there would be nothing left but meaningless debris.”

What is this remembrance, this memorial, or ritual memory? It is an application of the new theory of the sacrament. In this way, the ritual memory of the Church is sacrament, and thus has the faculty to make present the evoked reality. The Church, remembering Christ victorious through the assembled community, makes present within it, the glorious Christ together with His victory,

This theory is the origin of the change in the words of consecration. Having become “an account of the Institution,” these words are no longer spoken by the priest in the name of Christ priest, the sole cause of His presence and of His voluntary immolation, but in the name of the assembled Church, as he is “President” of this assembly.

This is how the new theories of the monk of Maria Laach were the theological foundation of the new mass of Pope Paul VI.

(Sources : Wikipédia/Le problème de la réforme liturgique – FSSPX.Actualités - 22/02/2020)